Bangladesh - Proshika>

"Video

can be for poor people. The tape can be a document to prove our position and we can use it like a

weapon."

"Video

can be for poor people. The tape can be a document to prove our position and we can use it like a

weapon."

--Shahnaz Begum

Bangladeshi village woman

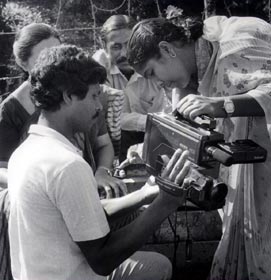

After participating in a C4C video training workshop at Proshika, Shahnaz Begum decided to film the story of her neighbor Aleya. The resulting tape, "The Life Struggle of Aleya," reflected many of the hardships shared by Bangladeshi women. Village screenings of the tape made a strong impression on viewers of all ages. In some communities, the videotape triggered public promises to neither pay nor take dowry - a pledge that is enforced by peer pressure.

In 1993 the videotape was among eight winners of the British Council's Women In Development video competition. Shahnaz went to Delhi to attend a screening of all the winning tapes. It was her first time outside of Bangladesh. "I was scared at first but then I felt strong," said Shahnaz. " I was afraid I would not be able to talk with the people I met in Delhi because they would be more educated and well dressed. But going to Delhi was one of the greatest experiences in my life!"

Shahnaz has many ideas about how video can be used as an organizing and mobilizing tool. While in Delhi she saw a program about people who came together to stand up against the police. "In this tape the people were so united the police couldn't do anything. Unity is so important." In sharing her experiences with the other Proshika video team members, Shahnaz observed, "All the other tapes in this competition used lots of make-up and acting. My tape was about the real life in Bangladesh."

[READ MORE about the videotape "The Life Struggle of Aleya" and its impact.]

Partner Organization Profile

Proshika, the third largest non-governmental organization in Bangladesh, has nearly three million members in villages and urban slums throughout the country. Women comprise a slight majority of the organization's membership. Human development is the core of Proshika's work and the basic organizing unit is a samiti, a group of up to 20 individuals. The group initiates a process of community consciousness-raising, analyzing the causes of poverty; it then develops collective savings and income-generating activities. Over a period of years, group members have achieved sustainable improvements in employment, health, education, social issues, agricultural practices, environment, and other areas. They also participate actively in local and district levels of decision making and planning.

Project Implementation

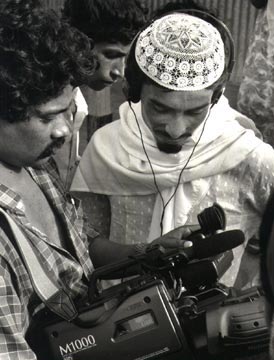

During an exploratory visit to Bangladesh in 1989, C4C and Proshika's Dhaka-based video team spent a day with several village women. The women offered many ideas for using video in their communities. One wished to interview leaders making promises; then, by showing the tape to the communities, she felt they could put pressure on the leaders to fulfill the promises they so often break. The women also proposed using video to expose exploitation of different kinds and share experiences between communities. From this visit emerged the plan of establishing rural video production units. The following year, C4C provided training for participants from seven different Proshika Area Development Centers (ADCs). Each ADC-based video team was comprised of two community members and one worker, and an equal number of men and women were involved. Each team was equipped with a VHS camcorder, a battery monitor, a set of playback equipment, a generator, and accessories.

The teams

produce tapes in a simple and time-efficient way, shooting their programs in-sequence, editing "in-camera."

The videos are shown in the field and at the centers; some are distributed throughout the organization.

While occasional follow-up training and technical support is available from Proshika's central

communication unit in Dhaka, the participatory video teams' work is locally oriented. What's more, the

use of video is fully integrated into the activities of the ADCs.

The teams

produce tapes in a simple and time-efficient way, shooting their programs in-sequence, editing "in-camera."

The videos are shown in the field and at the centers; some are distributed throughout the organization.

While occasional follow-up training and technical support is available from Proshika's central

communication unit in Dhaka, the participatory video teams' work is locally oriented. What's more, the

use of video is fully integrated into the activities of the ADCs.

For example, video provided a potent tool against the use of ‘current' nets, which some fishermen continue to employ illegally while the police look the other way. After several attempts to stop this practice, which had been destroying the livelihoods of people who fish legally, a Proshika cooperative enlisted the help of one of the organization's video teams. The team covertly taped the fishers setting current nets, and confronted them. The fishermen, upset about the tape, feared public humiliation. An agreement was reached: the video team agreed not to show the tape as long as the fishermen stopped using current nets. As one participatory video member observed, "Video cannot be bribed."

In another instance, video was used to effectively document - and gain compensation for - the loss of tree-plantations that had provided income for many Proshika members.

Joining Forces

When members of the Banchte Shekha video team visited Proshika's center in Singair, the group collaborated in documenting a local problem: the destruction of the community forestry projects of many Proshika members. Tree plantations along the roadside were being cut in order to widen the road. Proshika members had tried various tactics both to stop construction and to get compensation, but to no avail. The Banchte Shekha-Proshika team recorded the destruction of the plantations and interviewed people who had lost part of their livelihood as a result. Proshika has since used this jointly produced videotape to gain just compensation from the local government for the lost trees. The experience was satisfying for all of the participants and demonstrated the power of video - and of collaboration - in helping to solve local problems.

The Banchte

Shekha participatory video project was funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The Banchte

Shekha participatory video project was funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

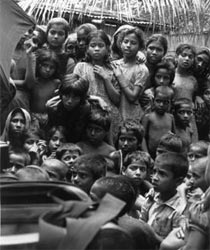

Other Proshika tapes challenge the necessity of dowry, document community accomplishments and present new income-generating activities for women. On viewing a Proshika tape about bamboo handicrafts, village women were amazed to see their sisters in another village working in an occupation traditionally reserved for men. They were excited by this tape and talked about getting a loan from their samiti to start a bamboo handicrafts trade. Village playbacks and the discussions that follow offer rich opportunities for organizing and mobilizing.

Creating "Instant Consciousness"

Over a hundred villagers crowded into the courtyard of a community center outside Mymensingh, Bangladesh. The crowd's excited chatter indicated that most of them were expecting to see a movie.

Asman, a local farmer and Proshika video producer, inserted the videotape into the VCR and the monitor flickered on. The villagers quickly recognized the features and faces of their own community. The program included frank interviews and information about the benefits of family planning, offered by people with whom audience members closely identified. After twenty minutes, the video came to a close and Asman stepped forward to retrieve the cassette. Some of the villagers stopped him and asked if they could see the tape again. He obliged.

A volley of questions opened the post-screening discussion. Asman was impressed by how thoroughly viewers had absorbed the program's contents, by how ready they were to relate its themes to their own personal situations. What's more, he realized that the videotape's immediacy had overcome barriers of literacy, enabling uneducated audience members to gain important information as easily as their schooled neighbors. As Asman later said to a C4C representative, it was as though the event created "instant consciousness".

Proshika's integration of participatory video into its work extends from tools, methods and management to ideology and ethics. Defining participatory video in a way that reflects the organization's core mission, Proshika formulated the following ten goals:

- To awaken people's human and ethical values.

- To ensure the participation of poor villagers and to value their thoughts and beliefs.

- To disprove the popular belief that poor villagers cannot use sophisticated technology and to create skills among these target people.

- To project the viewpoints of the villagers about social issues and to insure their participation.

- To point out the reasons why the poor are deprived and robbed of power.

- To ensure that participatory video remains true to life rather than being created as entertainment.

- To uphold the views of people who are alienated by the mass media.

- To show that grassroots people are capable of expressing their feelings and their problems.

- To raise people's consciousness by exchanging video programs among people of various regions.

- To show the processes from which people conquer poverty and to show the causes of poverty.

The Proshika video project is a rural development communication initiative remarkable in scope and in its level of local participation.

[Learn more about Proshika's success in using community video to create social change. For more details on this project, read "Powerful Grassroots Women Communicators" and "Media Ethics".]

The Proshika participatory video project was funded by the Ford Foundation.

© Communication for Change, Inc. 2003-2019. All rights reserved.